AIMAR PEREZ GALI

+

SARAH BROWNE

in conversation

|

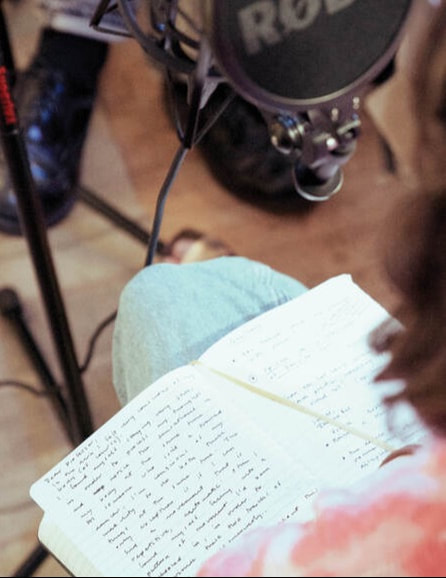

IN MAY 2019, WE INVITED CATALAN CHOREOGRAPHER AND DANCER AIMAR PEREZ GALI TO DUBLIN TO GIVE A WORKSHOP BASED ON HIS PRACTICE. MUCH OF AIMAR'S WORK FOCUSES ON THE IDEA OF EMBODIED INTELLIGENCE, AND HOW THE BODY FUNCTIONS AS AN ARCHIVE OF ITS EXPERIENCES. WHILE IN DUBLIN, AIMAR MET IRISH VISUAL ARTIST SARAH BROWNE, WHO TOOK PART IN THE WORKSHOP. DRAFF ARRANGED AN ARTIST TO ARTIST CONVERSATION BETWEEN SARAH AND AIMAR, BECAUSE WE SAW SIMILARITIES IN THEIR PRACTICES.

THE CONVERSATION WAS ORIGINALLY BROADCAST AS A PODCAST ON DUBLIN DIGITAL RADIO ON 30 SEPTEMBER 2019. YOU CAN LISTEN BACK OR READ THE TRANSCRIPT BELOW.

This conversation was broadcast on ddr. (Dublin Digital Radio) on September 30th 2019. To view the works mentioned by Sarah and Aimar during this conversation, visit this page.

|