GARY FARRELLY

|

|

Gary: Hi!

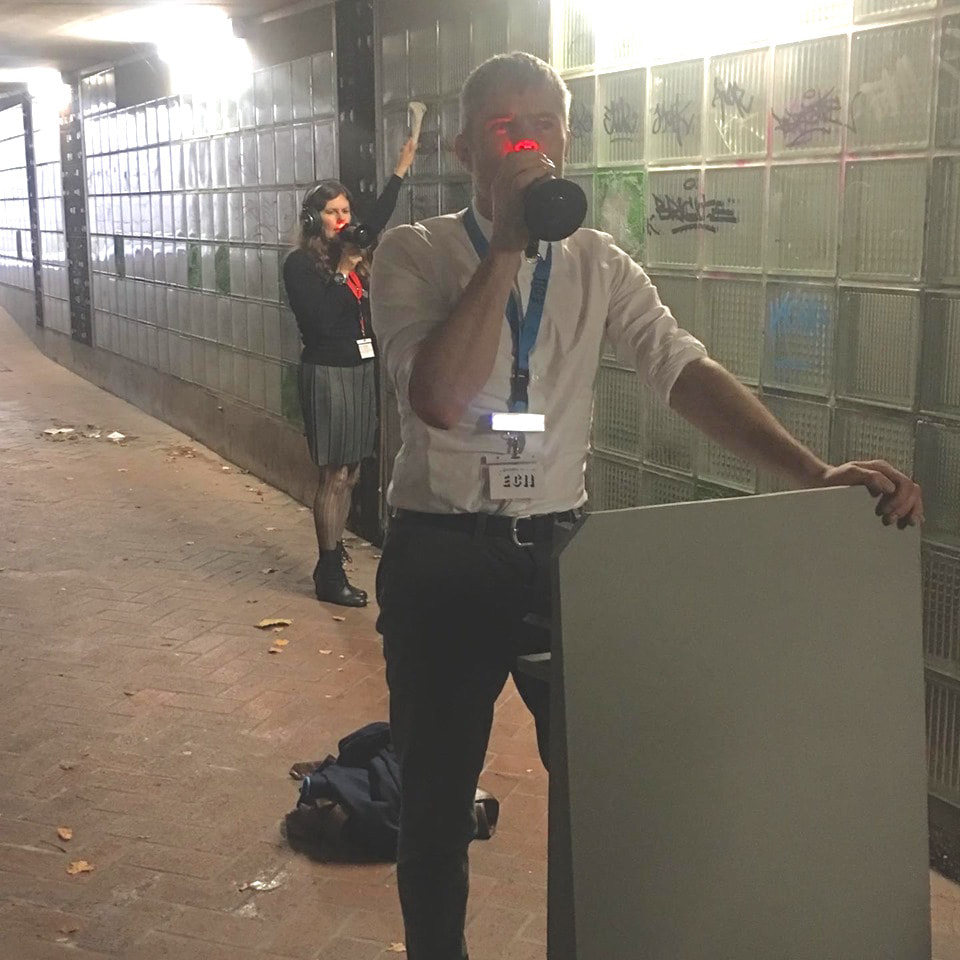

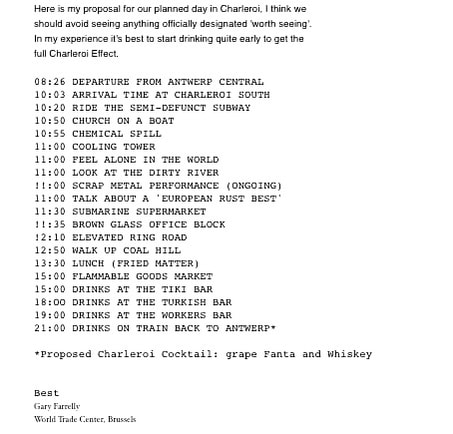

Laura: Hello, come on in! G: Oh it’s fucking wild out there! L: Yeah, it’s horrible out. Horrible. G: Hi, Gary. Nice to meet you! L: Hello, Laura, nice to meet you! G: I think we know each other from a very, very long time ago – I think we’re passing ships in the night from NCAD. L: I think so, many moons ago, in better weather. G: When I had jet black hair and a 15 inch waist. L: That is right. Yeah, yeah I do remember that. You had a glamorous air to you. G: I still have a glamorous air! So how are you doing? L: Good yes. It’s a rainy night in Wexford and it's a good night for chatting about art I guess. G: I’m glad we’re going to do this in the car. L: Yeah, yeah, cosy. It feels a little bit like a film actually. G: Yeah, well I think a lot of good exchanges happen in cars… strangers exchanging things in cars – drugs, sex, political secrets and now an artist blind date. L: An artist blind date, yeah totally, it’s like art dogging sort of, right? Kind of? Just lock the central lock there. [laughing] GARY AND LAURA MEETING IN A CAR

G: So I’ve been watching lots of your videos and I’m really, really fascinated by them. I’m very interested in this narrating of the experience of being an artist and the experience of kind of navigating the mechanisms and hierarchies and control mechanisms of the art world. But you’re narrating these things like, in the countryside using like, natural element and farm elements to tell these stories. I mean this is a really, really, really strange angle to take on things. I don’t know.

L: Yeah, I hope it can get stranger, maybe. I hope that maybe I can continue the narrative because I think those videos were made at a particular time when I felt very like angry and frustrated at the art world. But maybe in the last like two years suddenly I’m much more part of an art world. So I do have to deal with changing the energy slightly in the pieces. So it wouldn’t be fair for me to continue to channel frustration because now I am more involved in it. So it’s having to evolve a bit. G: Sure, well the impulse of need has changed. L: It has, it has. G: But what I thought was really interesting about these things, because I think this kind of work that somehow tackles head on the machinations of being an artist and being kind of disenfranchised and disempowered by like bigger, more powerful mechanisms than you and your practice… Or like, when people make work that does a meta-criticism of that, it can often be kind of super cynical and somehow, I don’t know… a bit gross. But I found there was something quite sincere in these works that you’re making and I found them really fascinating, because I didn’t see them as critical or performative works, I saw them as totally delusional works. I saw you in a field engaging with like, limpets on rocks and dwarf ponies in fields, talking about them as curators, but I didn’t think that this was some kind of shady comment on how the art world works. I really felt that in that moment you were actually like, simulating an art world experience that you were kind of longing for. I suppose I found that… yeah what’s the word… I find that ability to produce your own reality through your work to be really, really, well, useful. I saw you in a field engaging with limpets on rocks and dwarf ponies in fields, talking about them as curators...

|

G: I think it’s the sacred geometry in the chocolate itself and it’s a geometry that… it’s the basic kind of, fuckin first grade, bubble gum economics of occult architecture is you know, the pyramids. A pyramid shaped chocolate has a lot of power.

L: It does though when dissolved… Those pieces do fit so well into the centre on the top of your tooth… G: Into the hollowed out parts of your teeth. L: And I feel that somehow might transmit… or might be some sort of cavity filling device that could also tap into your… G: Well it would be a good way of administering fillings in the future, to put soft enamel in Toblerone bars. L: Yeah that is a good idea. Something you made me think of there when you were describing talking to the tunnels… but also, like it’s something I’m really interested in, and I think it is… like I hate talking about my work being against neoliberalism, like it is, but it’s so overused these days that it starts to lose potency. Sometimes, you know, like when you start talking about being an anti-capitalist and all this, which I am… But, there’s a book by a guy called Alan Counihan where he basically recorded all the field names in west Kerry, and so when I was doing these walking videos… G: Oh wow, the disappearing field names. L: Yeah… G: Ancient knowledges and all that. it’s the basic kind of, fuckin first grade, bubble gum economics of occult architecture, you know - the pyramids.

|