IN conversation:

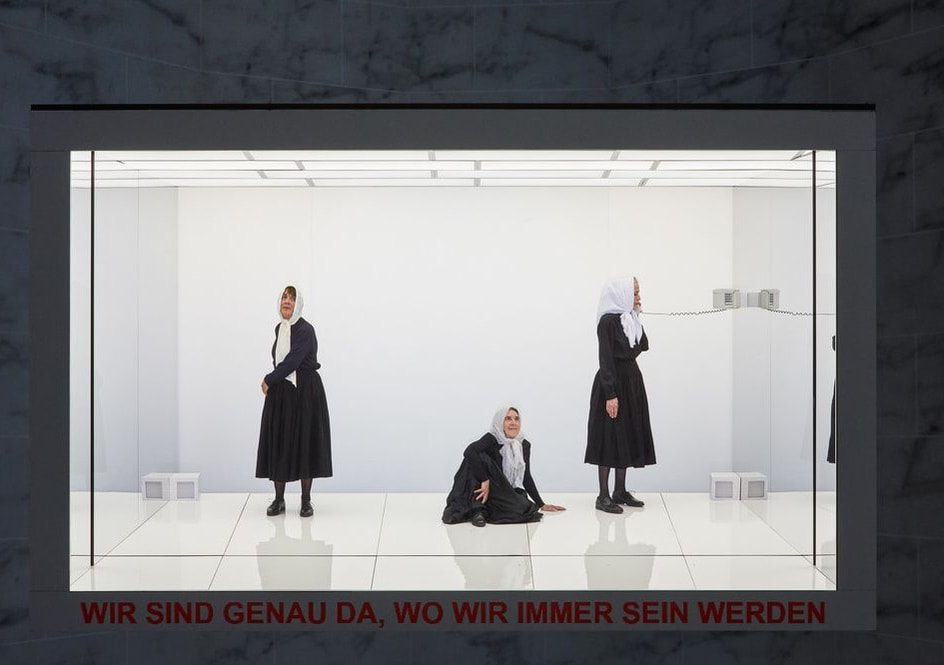

SUsANNE KENNEDY

|

SUSANNE KENNEDY IS A GERMAN THEATRE DIRECTOR KNOWN FOR HER EXPLORATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BODIES AND TECHNOLOGY IN HER WORK, OFTEN THROUGH FORMALLY EXPERIMENTAL ADAPTATIONS OF BOOKS, FILMS AND CLASSIC PLAYS. HER SHOWS MAKE USE OF MASKS, PLAYBACK, MULTIMEDIA AND THE DRAMATURGY OF THE INTERNET TO DE-FAMILIARISE OUR CONTEMPORARY EXPERIENCE.

HERE, SUSANNE IS IN CONVERSATION WITH DRAFF-ER AND FILM/THEATRE MAKER JOSE MIGUEL JIMENEZ ABOUT THE PARTS OF LIFE THAT FASCINATE HER AND HOW THEY FIND THEIR WAY INTO HER WORK.

|